![]() English version below / Vai alla versione italiana

English version below / Vai alla versione italiana

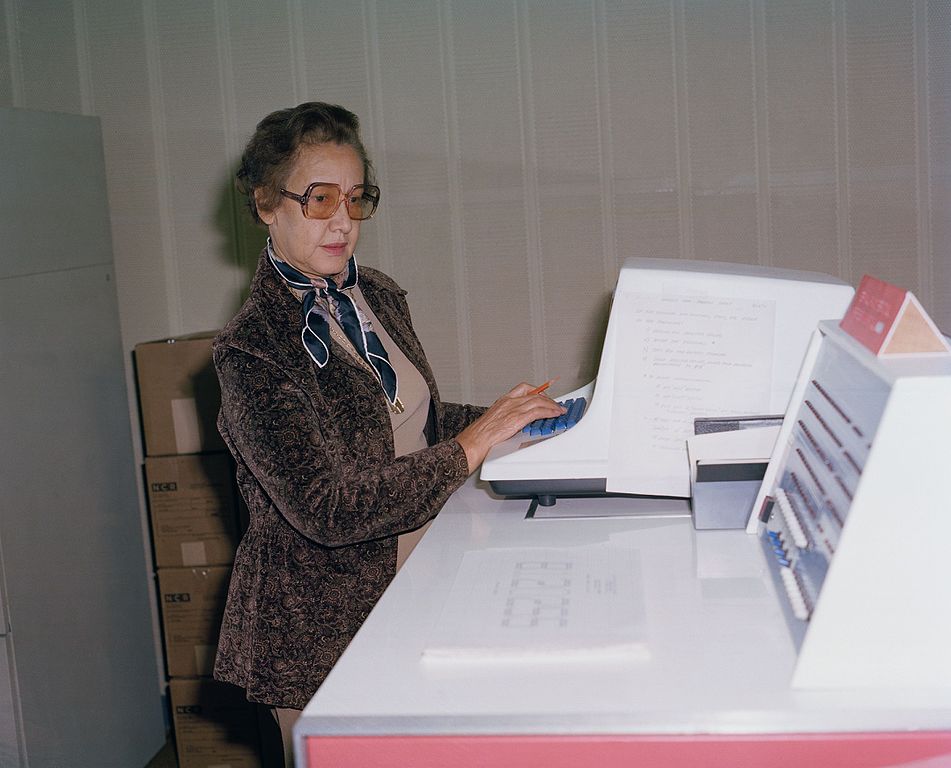

© NASA (Public Domain)

According to the Pew Research Center, the workforce employed in STEM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) sectors has grown 79% since 1990 and keeps steadily increasing to this day. As of now, ethnic minorities and women are severely underrepresented: Africans Americans make up just 6% of the STEM workforce, despite contributing 11% of the overall workforce; women make up only 14% of the engineers and 25% of the computer scientists, despite making up 47% of the overall workforce. Racism and sexism has kept ethnic minorities and women away from science for centuries, but now those two groups are finally looked on as a source of talents to be discovered. The difficulties the STEM companies face in finding qualified candidates induced the White House to launch in 2015 the initiative "Educate to Innovate” to encourage teenagers in science. Moreover, according to Forbes, tech companies are investing enormous amounts of resources in “coding boot camps” for minorities and girls: for instance, Google invested $50 million in 2014. Hopefully these initiatives might soon increase the number of African-American women in STEM jobs. Indeed, according to a ComptTIA survey, computer science is the favourite subject of 42% of African-American female respondents (compared to 20% of their white peers); 23% of the black respondents had considered a job in IT (compared to 19% of the white respondents).

Today we will tell the story of Katherine Johnson, mathematician and aerospace technologist at NASA. Born during racial segregation, she is a pioneer for women and African Americans in STEM fields. She worked in celestial mechanics and collaborated on several US space missions in the 60s, including the space flight of Alan Shepard, Apollo 11, and Apollo 13. In addition to the many NASA awards she received during her career, such as three NASA Special Achievement Awards, she also obtained three honorary doctorates and the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest US civilian award, in 2015. Her story is told in the book Hidden Figures: The Story of the African-American Women Who Helped Win the Space Race by Margot Lee Shetterley, adapted into a movie by Theodore Melfi.

Katherine Johnson née Coleman was born in 1918 in White Sulphur Springs, WV. She is the youngest of four; her mother was a school teacher and her father was a handyman at Greenbrier Hotel. As a child she was eager to attend school like her older brothers. She would eventually turn out to be a child prodigy: she started second grade at the age of 4 and finished 8th grade at the age of 10. In the 30’s, schools, neighborhoods, and facilities were segregated in the USA: Greenbrier County, where Katherine lived, had no high school open to African Americans. Katherine’s family did not give up and temporarily moved to Institute WV, about 200 km away, in order to allow her to continue her studies. At the age of 14, she obtained a high school degree with full scores and enrolled at West Virginia State College, a historically black college. William Schieffelin Claytor, one of the first African-American Ph.D.’s in mathematics, was a professor there. He immediately noticed Katherine’s talent, encouraged her to become a researcher, and personally monitored her: “Many professors tell you that you'd be good at this or that, but they don't always help you with that career path”, Katherine says. “Claytor made sure that I was prepared to be a research mathematician.” Since Katherine had already attended every single available maths course, Claytor decided to open new courses only for her. At the age of 18, Katherine already held a Bachelor of Science with honors with a double major in Mathematics and French. After the studies, she became a teacher, the best job available to her. In 1939 she married and left work to dedicate her time to her family; she resumed working in the 50's after her husband fell seriously ill.

In those years she heard from a relative that the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, the forerunner to NASA, was searching for African-American women to employ as "calculators". At the time, Johnson recalls, "computers wore skirts": every calculation needed by the engineers was done by hand by women. Johnson started working for the NACA in 1953, in the "Colored Computers" office, as it was mandatory for black people to use separated workspaces. Despite segregation, Katherine soon stood out for her acumen and her questions. She was assertive; she asked for, and obtained permission, to take part in the editorial meetings, until then a men-only affair: "I asked questions; I wanted to know why. They got used to me asking questions and being the only woman there." In 1956 her husband died. In 1958 NACA became NASA and the American space race began; Katherine got promoted to aerospace technologist in the Spacecraft Controls Branch of NASA. The institute was desegregated, but gender discrimination persisted: women still were not allowed to sign the technical reports they carried out. Johnson was the first to do it: "We needed to be assertive as women in those days - assertive and aggressive - and the degree to which we had to be that way depended on where you were", she says, "I had to be." In 1959 she married lieutenant James Johnson, war veteran, and became Katherine Johnson. Johnson worked for the NASA on the space mission of the first American Alan Shepard in 1961, on the 1969 Apollo 11 mission on the Moon, on the Apollo 13 mission, on the Space Shuttle program, the Earth Resources Satellite, and the first plans for a mission to Mars. Now she is happily retired; she likes travelling, spending time with her family, playing bridge and telling young people how beautiful it is to do science.

Last year, NASA named after her the newly opened "Katherine G. Johnson Computational Research Facility", a 3,400-square-meters building which cost $23 million. On her biography on the NASA website, we read: "NASA would not be what it is if not for you, Mrs. Johnson".

![]() Versione italiana a seguire / Back to English

Versione italiana a seguire / Back to English

© NASA (Public Domain)

Secondo il Pew Research Center negli USA l'occupazione nel settore STEM (scienze, tecnologia, ingegneria e matematica) è cresciuta del 79% dal 1990 ed è ancora in crescita. Al momento donne e minoranze etniche sono fortemente sottorappresentate: gli afroamericani costituiscono solo il 6% dei lavoratori STEM, nonostante siano ben l'11% della forza-lavoro totale; le donne sono solo il 14% degli ingegneri e il 25% degli informatici, nonostante rappresentino il 47% della forza-lavoro totale. Razzismo e sessismo hanno tenuto le minoranze etniche e le donne lontane dalla scienza per secoli, ma ora finalmente c'è chi guarda a questi due gruppi come ad un serbatoio di talenti ancora da scoprire. Le difficoltà delle aziende tecnologiche americane nel reperire personale qualificato hanno fatto sì che nel 2015 la Casa Bianca lanciasse un'apposita iniziativa "Educate to Innovate” per avvicinare gli adolescenti alle scienze. Inoltre, come riportato da Forbes, le compagnie tecnologiche stanno investendo enormi quantità di denaro in corsi di programmazione per minoranze e ragazze; nel 2014 la sola Google ha investito ben 50 milioni di dollari. Queste iniziative potrebbero portare presto ad un aumento del numero di donne afroamericane nel settore STEM. Infatti, secondo una survey ComptTIA, l'informatica è la materia preferita del 42% delle teenager afroamericane rispondenti (contro il 20% delle rispondenti di origine europea); il 23% delle rispondenti nere si dice interessata ad un lavoro nel settore (contro il 19% delle rispondenti bianche).

La storia che vi raccontiamo oggi è quella di Katherine Johnson, matematica e tecnologa aerospaziale della NASA. Nata durante la segregazione, è pioniera delle donne e degli afroamericani nelle discipline scientifiche. Si è occupata di meccanica celeste e ha collaborato a diverse missioni spaziali americane negli anni '60, fra le quali il volo nello spazio di Alan Shepard, Apollo 11 e Apollo 13. Ai diversi riconoscimenti ricevuti durante la sua carriera, fra i quali tre NASA Special Achievement Award, si aggiungono tre dottorati honoris causa e la Presidential Medal of Freedom, la più alta onorificenza civile americana, ottenuta nel 2015. La sua storia è raccontata nel libro Hidden Figures: The Story of the African-American Women Who Helped Win the Space Race di Margot Lee Shetterley, da cui è stato tratto l'omonimo film diretto da Theodore Melfi.

Katherine Coleman (poi Johnson) nasce nel 1918 a White Sulphur Springs (West Virginia). È l'ultima di quattro fratelli, sua madre è un'insegnante e suo padre svolge lavori manuali al Greenbrier Hotel. Da piccola è ansiosa di andare a scuola come fanno i suoi fratelli più grandi. Si rivelerà una bambina-prodigio: inizierà la scuola elementare a 4 anni e finirà le scuole medie a 10. Sono gli anni '30 e in America vige ancora la segregazione razziale: la Greenbrier County, dove vive Katherine, non ha scuole superiori aperte agli afroamericani. Pur di permetterle di proseguire gli studi, la famiglia di Katherine si trasferisce temporaneamente a Institute WV, a circa 200 km di distanza. A soli 14 anni la ragazzina si diploma a pieni voti e si iscrive al vicino West Virginia State College, un’università per afroamericani. Fra i suoi docenti ci sarà William Schieffelin Claytor, uno dei primi dottori in matematica afroamericani. Egli si accorge immediatamente del talento di Katherine, la incoraggia a diventare una ricercatrice e decide di seguirla personalmente: "Molti docenti ti dicono che sei bravo in questo o in quello, ma non sempre ti aiutano a proseguire in quel percorso lavorativo", dice Katherine, "Claytor voleva essere sicuro che fossi preparata per diventare una ricercatrice." Dal momento che Katherine ha già seguito tutti i corsi di matematica offerti, Claytor decide di tenere dei nuovi corsi apposta per lei. A soli 18 anni Catherine ha già in mano un Bachelor of Science in matematica e francese, a pieni voti. Finiti gli studi, fa l'insegnante, il miglior lavoro a cui puo’ avere accesso. Nel 1939 si sposa e lascia l’insegnamento per occuparsi della famiglia; riprenderà negli anni '50 dopo che suo marito si ammala gravemente.

In quegli anni viene a sapere da un parente che la National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, l'ente predecessore della NASA, sta cercando donne afroamericane da assumere come "calcolatrici". A quei tempi, ricorda Johnson, i "computer avevano le gonne": tutti i conti di cui avevano bisogno gli ingegneri venivano svolti a mano, e dalle donne. Johnson inizia a lavorare per NACA nel 1953 nell'ufficio delle "Calcolatrici di Colore" - per legge le persone di colore dovevano lavorare in spazi separati dai bianchi. Malgrado la segregazione, Katherine si fa presto notare per la sua perspicacia e le sue domande. E’ una donna che sa il fatto suo, chiede e ottiene di partecipare agli editorial meetings, fino ad allora riservati agli uomini: "Facevo domande; volevo capire i "perché". Si abituarono al fatto che facevo domande ed ero l'unica donna presente ". Nel 1956 suo marito muore e resta vedova. Nel 1958 la NACA diventa NASA ed inizia la corsa americana allo spazio; Katherine viene promossa a tecnologa aerospaziale nella Spacecraft Controls Branch della NASA. Cade la segregazione all'interno dell'istituto, ma persistono le discriminazioni di genere: alle donne non era ancora consentito firmare i rapporti tecnici che svolgevano. Sarà Johnson la prima a farlo: "Dovevamo essere decise come donne a quei tempi - decise e aggressive - e il punto fino a cui dovevamo esserlo dipendeva dalla posizione in cui ci trovavamo", dice, "Io dovevo esserlo." Nel 1959 sposa il tenente James Johnson, veterano di guerra, e ne assume il cognome. Per la NASA Katherine Johnson lavora alla missione nello spazio del primo astronauta americano Alan Shepard nel 1961, alla missione Apollo 11 sulla Luna del 1969, alla missione Apollo 13, al programma Space Shuttle, Earth Resources Satellite e ai primi piani per una spedizione su Marte. Ora è felicemente pensionata; le piace viaggiare, passare il tempo con la sua famiglia, giocare a bridge e raccontare ai giovani quanto è bello fare scienza.

Lo scorso anno la NASA ha inaugurato in suo onore la "Katherine G. Johnson Computational Research Facility", un edificio di oltre 3400 metri quadrati costato 23 milioni di dollari. Sulla sua biografia sul sito della NASA si legge: “la NASA non sarebbe ciò che è se non fosse stato per lei, Mrs. Johnson”.

Valentina is a Postdoc in Geometric Topology at Heidelberg Universität in Germany. Having grown up in a small town in Salento, she got interested in maths as a teenager thanks to the Italian Maths Olympiad and a noisy 56k modem. After being a contestant in the Italian Finals in Cesenatico, she started solving the beautiful problems posted on the OliForum and its mailing list. She has lived abroad since 2010, and has worked in France and the US, where she also attended many events and panels discussing the gender gap in STEM fields. When she is not doing maths, she enjoys reading good literature, traveling, volunteering and dancing rueda de casino.

Valentina is a Postdoc in Geometric Topology at Heidelberg Universität in Germany. Having grown up in a small town in Salento, she got interested in maths as a teenager thanks to the Italian Maths Olympiad and a noisy 56k modem. After being a contestant in the Italian Finals in Cesenatico, she started solving the beautiful problems posted on the OliForum and its mailing list. She has lived abroad since 2010, and has worked in France and the US, where she also attended many events and panels discussing the gender gap in STEM fields. When she is not doing maths, she enjoys reading good literature, traveling, volunteering and dancing rueda de casino.